I studied art on an athletic scholarship for basketball at Pepperdine College. In 1965 I transferred to the University of Southern California. Four years in architecture, dropped out, landed in the ceramics department and finished a BFA in ceramics in 1970. It was there that I met my life-partner, Deborah Smith.

Deborah and I discovered in each other an interest in the philosophy of the East and would meet again in India, Pondicherry, at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. An ashram secretary, aware of Deborah’s Japanese experience, asked her if she would start a pottery for the ashram. “Yes,” she said, “if my friend comes and agrees to build a kiln.”

The Golden Bridge Pottery was founded in a 10ft x 20ft palm-leaf shed in 1971 by Deborah Smith on wasteland leased by the ashram adjacent to the railway line to Villapurm, selected by The Mother who said it was a lucky spot, Deborah intended to work as an individual studio potter. I thought I was going to build her a kiln and move on. In fact I became a co-founder. We had no idea what we were beginning, but in 1972 Deborah’s mother visited and prophetically called our fledgling efforts—without a hint of sarcasm—the “South Indian Ceramic Center.” Today, former GBP students are a pivotal element in the creation of the Indian Ceramic Triennale.

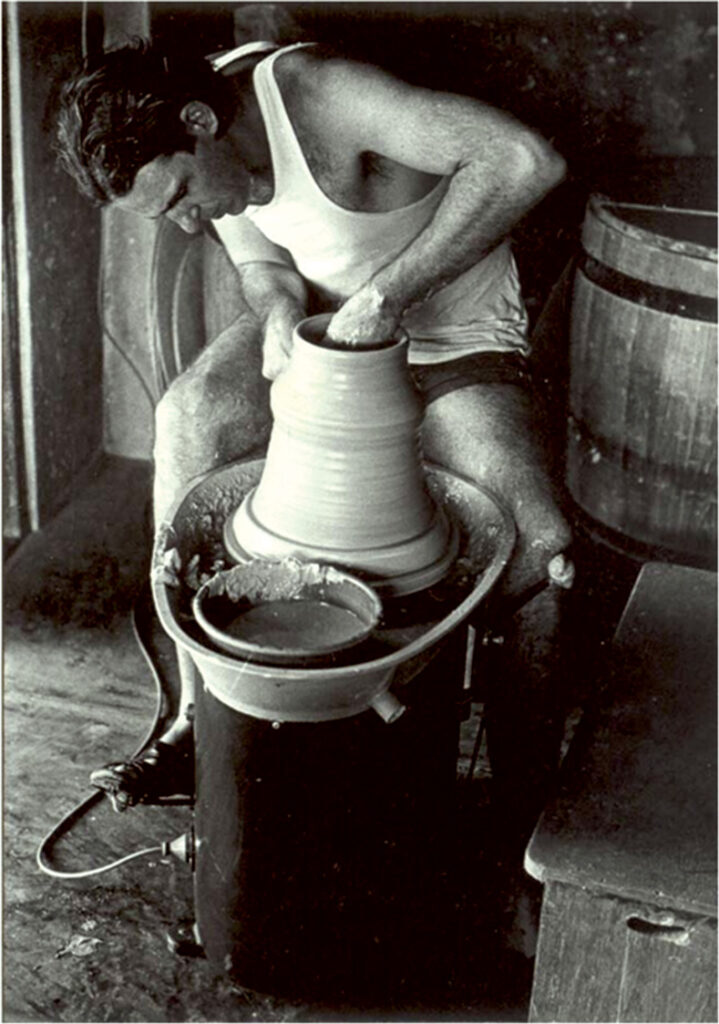

In Bizen pots are unglazed glaze and fired with wood for days, yielding a result that in Japan is highly treasured but in India is characterized at best as ‘rustic.’ My ceramic begging was a mix of Carlton Ball/60s/California/Japanese/cone ten/functional stoneware with a dash of Clayton Bailey funk. And sculpture. In 1971, in South India, neither Bizenware nor ceramic sculpture seemed appropriate. Deborah was greatly influenced by Hamada, by his aesthetic and his way of working. The Golden Bridge Pottery was loosely modelled on her Mashiko experience.We had books. Leach and Rhodes mainly. Nigel Wood’s Oriental Glazes. I built a 30cft. catenary cross-draft kiln fired with kerosene. Power in those days was unreliable. Kick wheels, clay slaked and sieved into terracotta drying tanks, and natural-draft kilns require no power and remained adequate for our production as it expanded. Raw materials were sourced from India’s well-developed heavy clay industry. After exhausting excursions by bicycle in the treacherous heat of May in search of a local clay source, romance gave way to expedience. We mix a stoneware body; fireclay, ball clay, china clay, quartz and feldspar purchased directly from mines in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat, two types of local red clay and river sand are from local sources. For ten years Deb and I worked together with two or three apprentices drawn from the Ashram community. As apprentices left to establish their own studios, we decided to train young men from the adjacent village. Deborah, now retired, managed up to seventeen workers producing a line of more than two hundred functional stoneware forms on orders that were more than she could fill. She did all the decoration of GBP ware after 1987, when I took my fired-building experiments beyond the pottery compound. We now fire with wood—casuarina, grown locally as a fuel crop—in a 70cft. car kiln with Bourry fire-boxes modified to preheat primary combustion air. A new craft tradition has emerged: “Pondicherry Pottery.”

In 1983 we opened a seven-month course for students. We turn students loose into abundant infrastructure and give enough direction to get them off the ground. Kilns are big enough to get real work into, wheels are numerous, and space is open and extensive, all providing an opportunity to get deep enough into material and process to develop something of value.

We invite different approaches by bringing in other artists for workshops. Though we do preach GBP standards, we do not expect students to remain stuck in a GBP aesthetic.